Anyway, about four years ago I was looking for an alternative critter when I remembered someone at a party once mentioning sea monkeys, a hybrid species of brine shrimp suitable for keeping at home. Artemia nyos are very cheap to purchase and look after, with little in the way of paraphernalia required to keep them alive. (Incidentally, in addition to not being monkeys - obviously - they also don't live in the sea; the parent species are native to saline lakes.)

The most noticeable difference for me after Triops is that they don't require the frequent water changes that tadpole shrimp do. What's more they live somewhat longer: I've managed lifespans over six months, compared to just half that for Triops. In addition, sea monkeys can live in tiny tanks and so are the ultimate in pint-sized pets - or to be more accurate, three-quarters of a pint-sized pets.

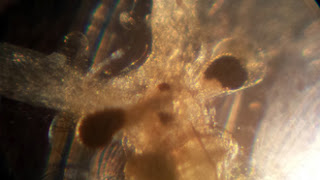

Being only half the size of Triops, they require close-up observation; even with a themed tank, you are unlikely to get anything like a tropical aquarium experience. What's more, they refrain from digging motions and the other more interesting traits found in tadpole shrimp, mostly swimming on their backs, mating, or fanning through particles at the bottom of the tank for food. In fact, apart from some aquabatics, sea monkeys don't appear to have an awful lot to offer. For example, they don't have the range of behaviour that I've observed in individual tadpole shrimp, such as exuberant laps or hiding behind objects in the tank. Once you've observed them for a few months, the novelty begins to wear off, especially when they start dying in droves.

Therefore I thought that they might offer some interesting opportunities for scientific research with the minimum of apparatus. I initially tried a few changes - such as keeping a spotlight on at night during the first week of a new tank, partially for the warmth - but this was too informal to count as good research. I then started keeping a diary of the tanks, leading to a series of experiments aimed at finding the optimal conditions for maximising both number of individuals and longevity. I can't say that after three years' of research I have exactly found the brine shrimp equivalent of the elixir of youth but I've certainly enjoyed playing biologist, even if my methodology and laboratory conditions aren't quite up to professional standard (insert smiley here if you like).

Towards the end of the research period I explored some websites where other owners/breeders/keepers (delete as appropriate) had also experimented on the animals and their eggs. These raised some interesting questions, including concerns over the amoral nature of some practical science. Even so, it all gave me a good opportunity for to write this post!

For those without sea monkey experience, here's a brief summary of what is involved in their upkeep:

- A commercial water conditioner is added to a 12 ounce/350ml tank containing non-chlorinated (in my case, bottled) water, although the conditioner sachet often appears to include some eggs.

- A separate sachet of eggs is added a day or so later. The eggs usually hatch between two and five days after this, the water temperature directly correlating to the speed of hatching.

- Some days after hatching, the shrimp begin to be fed miniscule amounts of powdered algae, the frequency depending on the number of adults.

- The water level is topped up once every month or so with bottled water.

- Ideally, the tank is aerated every one or two days, in my case using an 'aqua leash' included with one of the tank kits.

So a fairly simple care regimen, then. None of my tanks have ever had more than seven adults at a time, which contrasts markedly with the congested tanks I've seen in internet videos. Whether it is the absence of light at night or cooler temperatures in general compared to other owners I'm not sure, but the lack of numbers was certainly not through a shortage of aeration or appropriate amounts of food, except during several months' of experiments as described in this summary of my research:

Q1: Could I raise sea monkeys using a ratio of water conditioner to water 30% lower than recommended?

A1: Negative. No eggs hatched. (See, I'm trying to use the correct scientific tone...)

Q2: Could I raise them using a tank substrate?

A2: Not wanting to waste eggs and conditioner I only performed this once, using finely crushed sea shells thoroughly rinsed in bottled water. No eggs hatched.

Q3: Did the brand of bottled water (with differing amounts of dissolved solids) make any difference to hatching numbers or longevity?

A3: Not noticeably.

Q4: Did a mature, mixed female-male population produce more hatchlings than a female-only population?

A4: Marginally, although after the initial hatching once a tank was set up, very few later nauplii survived more than a month.

Q5: Were, as I had read, the shrimp more photo-reactive when the tank was crossed by narrow beams of light in an otherwise dark environment?

A5: I saw very little evidence for this.

Q6: Did the distance from a window and direction/angle of daylight affect numbers?

A6: This was tricky, since around ninety minutes on a sunny window sill was all I allowed in order to prevent a tank transforming into a serving of Bisque du mer singe. But there was little evidence to suggest the amount of light altered the number or longevity of the population.

Q7: Did the tank temperature affect hatching numbers?

A7: I didn't want to use a normal tank thermometer, the tanks being so small, so I only had the fairly inaccurate sort that stick on the outside of aquaria. The only correlation I saw was that on colder nights it was better to keep tanks away from the window sill where it was obviously chillier than elsewhere in the room.

Q8: Did the frequency of aeration affect the population?

A8: I tried various permutations, from twice daily, to three times per week, to just once a week or even less, but this appeared to make little difference. Then again, I wasn't successful in raising more than five nauplii in any one 'mature' tank at a time, and so perhaps the population was too low to require greater oxygenation.

Q9: Did the feeding frequency affect the population?

A9: Again, I tried a range of schedules over several years, from once every five days to once per month. However, the low adult populations meant there was never any danger of starvation: their digestive tracts always looked full and at various times, individuals were accompanied by long strings of excrement. Hmm, nice!

Q10: Could I raise sea monkeys using a homemade water conditioner?

A10: This was the last experiment I undertook. I scoured the internet for the correct quantities of ingredients before trying several sea salt and baking soda ratios, but no eggs hatched after a month.

After I had completed these experiments, I searched the internet and found that my methods were rather tame compared to some of the research conducted on sea monkeys, and indeed brine shrimp species in general. Therefore here are some other potential experiments for those with the inclination:

- Try other foods, such as baker's yeast

- Try rain water or using self-created distilled water

- Conduct water quality tests (aquarium kits such as for the ammonia/nitrate/nitrite cycle)

- Egg hardiness, such as freezing and microwaving before attempting to hatch them*

- Different oxygenation techniques, such as blowing (not exhaling) a fresh intake of air through a straw.

Although they are claimed to be easy to raise - indeed, other species are used for toxicity testing and their eggs subjected to cosmic ray experiments - I don't seem to have had much luck with breeding large populations (or in a rather more scientific tone, the condition of my tanks has proved to be sub-optimal). When one adult died, most of the other adults usually followed within a week. Despite frequent matings, lasting hours or even days and repeated several times per week, I've never seen more than five nauplii hatch in the same week in a mature tank. In addition, most seem to die after the first few instars, with very few reaching maturity. On the other hand, I once saw a tank with fully-grown shrimp belonging to a child who had added food daily but never aerated. Despite the water being obscured by thick algal growths, a few individuals managed to hang on in a presumably very oxygen-poor environment. Yet my zealous attention has seemingly had little impact!

So whilst they don't live up to the cuddliness of say guinea pigs, they are extremely useful as err...experimental guinea pigs, as it were, for the amateur biologist. And yes, watching the aquabatics can be fun, too!