Following on from last month's exploration of external factors inhibiting the scientific enterprise, I thought it would be equally interesting to examine issues within the sector that can negatively influence STEM research. There is a range of factors that vary from the sublime to the ridiculous, showing that science and its practitioners are as prey to the whims of humanity as any other discipline.

1) Conservatism

The German physicist Max Planck once said that a "new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it." With peer review of submitted articles, it's theoretically possible that a new hypothesis could be prevented from seeing the light of day due to being in the wrong place at the wrong time; or more precisely, because the reviewers personally object to the ideas presented.

Another description of this view is that there are three stages before the old guard accept the theories of the young turks, with an avant garde idea eventually being taken as orthodoxy. One key challenge is the dislike shown by established researchers to outsiders who promote a new hypothesis in a specialisation they have no formal training in.

A prominent example of this is the short shrift given to meteorologist Alfred Wegener when he described continental drift to the geological establishment; it took over thirty years and a plethora of evidence before plate tectonics was found to correlate with Wegener's seemingly madcap ideas. More recently, some prominent palaeontologists wrote vitriolic reviews of the geologist-led account of the Chicxulub impact as the main cause of the K-T extinction event.

This also shows the effect impatience may have; if progress in a field is slow or seemingly negative, it may be prematurely abandoned by most if not all researchers as a dead end.

2) Putting personal preferences before evidence

Although science is frequently sold to the public as having a purely objective attitude towards natural phenomena, disagreements at the cutting edge are common enough to become cheap ammunition for opponents of STEM research. When senior figures within a field disagree with younger colleagues, it's easy to see why there might be a catch-22 situation in which public funding is only available when there is consensus and yet consensus can only be reached when sufficient research has as placed an hypothesis on a fairly firm footing.

It is well known that Einstein wasted the last thirty or so years of his life trying to find a unified field theory without including quantum mechanics. To his tidy mind, the uncertainty principle and entanglement didn't seem to be suitable as foundation-level elements of creation, hence his famous quote usually truncated as "God doesn't play dice". In other words, just about the most important scientific theory ever didn't fit into his world picture - and yet the public's perception of Einstein during this period was that he was the world's greatest physicist.

Well-known scientists in other fields have negatively impacted their reputation late in their career. Two well-known examples are the astronomer Fred Hoyle and microbiologist Lynn Margulis. Hoyle appears to have initiated increasingly fruity ideas as he got older, including the claim that the archaeopteryx fossil at London's Natural History Museum was a fake. Margulis for her part stayed within her area of expertise, endosymbiotic theory for eukaryotic cells, to claim her discoveries could account for an extremely wide range of biological functions, including the cause of AIDS. It doesn't take much to realise that if two such highly esteemed scientists can publish nonsense, then uninformed sections of the public might want to question the validity of a much wider variety of established scientific truths.

3) Cronyism and the academic establishment

While nepotism might not appear often in the annals of science history, there have still been plenty of instances in which favoured individuals gain a position at the expense of others. This is of course a phenomenon as old as natural philosophy, although thankfully the rigid social hierarchy that affected the careers of nineteenth century luminaries such as physicist Michael Faraday and dinosaur pioneer Gideon Mantell is no longer much of an issue.

Today, competition for a limited number of places in university research faculties can lead to results as unfair as in any humanities department. A congenial personality and an ability to self-publicise may tip the balance on gaining tenure as a faculty junior; scientists with poor interpersonal skills can fare badly. As a result, their reputation can be denigrated even after their death, as happened with DNA pioneer Rosalind Franklin in James Watson's memoirs.

As opponents of string theory are keen to point out, graduates are often forced to get on bandwagons in order to gain vital grants or academic tenure. This suggests that playing safe by studying contemporary ‘hot' areas of research is preferred to investigating a wider range of new ones. Nobel Laureate and former Stephen Hawking collaborator Roger Penrose describes this as being particularly common in theoretical physics, whereby the new kids on the block have to join the entourage of an establishment figure rather than strike out with their own ideas.

Even once a graduate student has gained a research grant, it doesn't mean that their work will be fairly recognised. Perhaps the most infamous example of this occurred with the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics. One of the two recipients was Antony Hewish, who gained the prize for his "decisive role in the discovery of pulsars”. Yet it was his student Jocelyn Bell who promoted the hypothesis while Hewish was claiming the signal to be man-made interference.

4) Jealousy and competitiveness

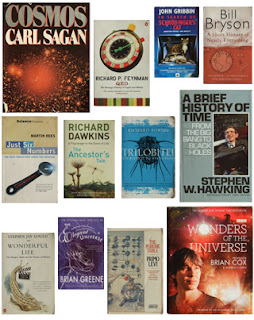

Although being personable and a team player can be important, anyone deemed to be too keen on self-aggrandising may attract the contempt of the scientific establishment. Carl Sagan was perhaps the most prominent science communicator of his generation but was blackballed from the US National Academy of Sciences due to being seen as too popular! This is despite some serious planetary astronomy in his earlier career, including work on various Jet Propulsion Laboratory probes.

Thankfully, attitudes towards sci-comm have started to improve. The Royal Society has advocated the notion that prominent scientists should become involved in promoting their field, as public engagement has been commonly judged by STEM practitioners as the remit of those at the lower end of scientific ability. Even so, there remains the perception that those engaged in communicating science to the general public are not proficient enough for a career in research. Conversely, research scientists should be able to concentrate on their work rather than having to spend large amounts of their time of seeking grants or undertaking administration - but such ideals are not likely to come to in the near future!

5) Frauds, hoaxes and general misdemeanours

Scientists are as human as everyone else and given the temptation have been known to resort to underhand behaviour in order to obtain positions, grants and renown. Such behaviour has been occurring since the Enlightenment and varies from deliberate use of selective evidence through to full-blown fraud that has major repercussions for a field of research.

One well-known example is the Piltdown Man hoax, which wasn't uncovered for forty years. This is rather more due to the material fitting in with contemporary social attitudes rather than the quality - or lack thereof - of the finds. However, other than generating public attention of how scientists can be fooled, it didn't damage science in the long run.

A far more insidious instance is that of Cyril Burt's research into the heritability of intelligence. After his death, others tried to track down Burt's assistants, only to find they didn't exist. This of course placed serious doubt on the reliability of both his data and conclusions, but even worse his work was used by several governments in the late twentieth century as the basis for social engineering.

Scandals are not unknown in recent years, providing ammunition for those wanting to deny recognition of fundamental scientific theories (rarely the practical application). In this age of social media, it can take only one person's mistake - deliberate or otherwise - to set in motion a global campaign that rejects the findings of science, regardless of the evidence in its favour. As the anti-vaccination lobby have proven, science communication still has long way to go if we are to combine the best of both worlds: a healthy scepticism with an acceptance of how the weird and wonderful universe really works, and not how we would like it to.