Reading the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom's thought-provoking book Superintelligence, I was struck by his description of the variation of human intellect (from as he put it, Einstein to the village idiot) as being startling narrow when compared to the potential range of possible intelligences, both biological and artificial.

The complexity of animal brains has been analysed by both quantitive and qualititive methods, the former dealing with such measurements as the number of neurons while the latter looks at behaviour of members of a species, both in the wild and under laboratory conditions. However, a comparison of these two doesn't necessarily provide any neat correlation.

For example, although mammals are generally - and totally incorrectly - often described as the pinnacle of creation due to their complex behaviour and birth-to-adult learning curve, the quantitive differences in neural architecture within mammals are far greater than those between amphibians and some mammalian families. In addition, there are many birds, mostly in the Psittacidae (parrot) and Corvidae (crow) families, that are both quantitatively and qualitatively superior to most mammals with the exception of some primates.

I think it was the essays of evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould that introduced me to the concept of EQ or encephalisation quotient, which is a label for the brain-mass to body-mass ratio. On these terms, the human brain is far larger than nearly all other species with a similar sized body, the exception (perhaps not surprisingly) being dolphins.

However, it's difficult to draw accurate conclusions just from examination of this general trend: both the absolute size of the brain and neuron density play a fundamental role in cognitive powers. For example, gorillas have a lower EQ that some monkeys, but being a large ape have a far greater brain mass. It could be said then, that perhaps beyond a certain mass the absolute brain size renders the EQ scale of little use. A 2009 study found that different rules for scaling come into play, with humans also having a highly optimal use of the volume available with the cranium, in addition to the economical architecture common among primates.

As historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari has pointed out, the development of farming, at least in Eurasia, went hand in hand with the evolution of sophisticated religious beliefs. This led to a change in human attitudes towards the other animals, with a downplay of the latter's emotional needs and their categorisation as inferior, vassal species in a pre-ordained (read: divinely-given) chain of being.

By directly connecting intelligence - or a lack thereof - to empathy and emotions, it is easy to claim that domesticated animal species don't mind their ruthless treatment. It isn't just industrial agriculture that makes the most of this lack of empathy today; I've seen small sharks kept in a Far Eastern jewellery store (i.e. as decoration, not as future food) in tanks barely longer than the creature's own body length.

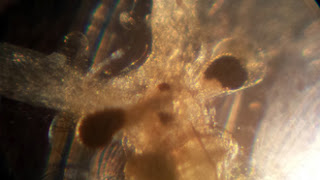

Although the problem-solving antics of birds such as crows are starting to redress this, most people still consider animal intelligence strictly ordered by vertebrate classes, which leads to such inaccuracies as the 'three second goldfish memory'. I first noticed how incorrect this was when keeping freshwater invertebrates, namely shield shrimp A.K.A. triops, almost a decade ago. Even these tiny creatures appear to have a range of personalities, or perhaps I should say - in an effort to avoid blatant anthropomorphizing - a wide variety of behaviour.

Now on the verge of setting up a tropical aquarium for one of my children, I've been researching what is required to keep fish in fairly small tanks. I've spoken to various aquarium store owners and consulted numerous online resources, learning in the process that the tank environment needs to fulfill certain criteria. There's nothing in usual in this you might think, except that the psychological requirements need to be considered alongside the physical ones.

For example, tank keepers use words such as 'unhappy' and 'depression' to describe what happens when schooling fish are kept in too small a group, active swimmers in too little space and timid species housed in an aquarium without hiding places. We do not consider this fish infraclass - i.e. teleosts - to be Einsteins (there's that label again) of the animal kingdom, but it would appear we just haven't been observing them with enough rigour. They may have minute brains, but there is a complexity that suggests a certain level of emotional intelligence in response to their environment.

So where does all this leave us Homo sapiens, masters of all we survey? Neanderthal research is increasingly espousing the notion that in many ways these extinct cousins/partial ancestors could give us modern humans a run for our money. Perhaps our success is down to one particular component of uniqueness, namely our story-telling ability, a product of our vivid imagination.

Simply because other species lack this skill doesn't mean that they don't have any form of intellectual ability; they may indeed have a far richer sense of their universe than we would like to believe. If our greatest gift is our intelligence, don't we owe it to all other creatures we raise and hold captive to make their lives as pleasant as possible? Whether it's battery farming or keeping goldfish in a bowl, there's plenty we could do to improve things if we consider just what might be going on in the heads of our companion critters.