The old days of senior figures pontificating as if in a university lecture theatre are long gone, with blackboard diagrams and scruffy hair replaced by presenters who are keen to prove their non-geek status via participation in what essentially amount to danger sports in the name of illustrating examples. Okay, so the old style could be very dry and hardly likely to be inspirational to the non-converted, but did Orbit really need a non-scientist when Helen Czerski (who is hardly new to television presenting) can deliver to camera whilst skydiving? In addition, there are some female presenters, a prominent British example being Alice Roberts, who have been allowed to solely present several excellent series, albeit involving science and humanities crossovers (and why not?)

But going back to Kate Humble, some TV presenters seems to cover such a range of subject matter that it makes you wonder if they are just hired faces with no real interest (and/or knowledge) in what they are espousing: “just read the cue cards convincingly, please!” Richard Hammond - presenter of light entertainment show Top Gear and the (literally) explosive Brainiac: Science Abuse has flirted with more in-depth material in Richard Hammond's Journey To The Centre Of The Planet, Richard Hammond's Journey To The Bottom Of The Ocean and Richard Hammond's Invisible Worlds. Note the inclusion of his name in the titles – just in case you weren't aware who he is. Indeed, his Top Gear co-presenter James May seems to be genre-hopping in a similar vein, including James May's Big Ideas, James May's Things You Need to Know, James May on the Moon and James May at the Edge of Space amongst others, again providing a hint as to who is fronting the programmes. Could it be that public opinion of scientists is poor enough - part geek, part Dr Strangelove - to force producers to employ non-scientist presenters with a well-established TV image, even if that image largely consists of racing cars?

Having said that, science professionals aren't infallible communicators: Sir David Attenborough, a natural sciences graduate and fossil collector since childhood, made an astonishing howler in his otherwise excellent BBC documentary First Life. During an episode that ironically included Richard 'Mr Trilobite' Fortey himself, Sir David described these organisms as being so named due to their head/body/tail configuration. In fact, the group's name stems somewhat obviously from tri-lobes, being the central and lateral lobes in their body plan. It was an astounding slip up and gave me food for thought as to whether anyone on these series ever double checks the factual content, just to make sure it wasn't copied off the back of a cereal packet.

Another possible reason for using non-science presenters is that in order to make a programme memorable, producers aim to differentiate their expositors as much as possible. I've already discussed the merits of two of the world's best known scientists, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and the unique attributes they bring to their programmes, even if in Dawkins' case this revolves around his attitude to anyone who has an interest in any form of unproven belief. I wonder if he extends his disapprobation to string theorists?

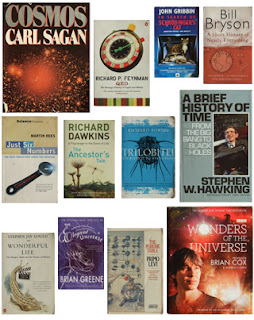

What is interesting is that whereas the previous generation of popular science expositors achieved fame through their theories and eventually bestselling popularisations, the current crop, of whom Helen Czerski is an example, have become well-known directly through television appearances. That's not to say that the majority of people who have heard of Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins have read The Selfish Gene or A Brief History of Time. After all, the former was first published in 1976 and achieved renown in academic circles long before the public knew of Dawkins. Some estimates suggest as little as 1% of the ten million or so buyers of the latter have actually read it in its entirety and in fact there has been something of a small industry in reader's companions, not to mention Hawking's own A Briefer History of Time, intended to convey in easier-to-digest form some of the more difficult elements of the original book. In addition, the US newspaper Investors Business Daily published an article in 2009 implying they thought Hawking was an American! So can you define fame solely of being able to identify a face with a name?

In the case of Richard Dawkins it could be argued that he has a remit as a professional science communicator, or at least had from 1995 to 2008, due to his position during this time as the first Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science. What about other scientists who have achieved some degree of recognition outside of their fields of study thanks to effective science communication? Theoretical physicist Michio Kaku has appeared in over fifty documentaries and counting and has written several bestselling popular science books , whilst if you want a sound bite on dinosaurs Dale Russell is your palaeontologist. But it's difficult to think of any one scientist capable of inspiring the public as much as Carl Sagan post- Cosmos. Sagan though was the antithesis of the shy and retiring scientist stereotype and faced peer accusations of deliberately cultivating fame (and of course, fortune) to the extent of jumping on scientific bandwagons solely in order to gain popularity. As a result, at the height of his popularity and with a Pulitzer Prize-winning book behind him, Sagan failed to gain entry to the US National Academy of Sciences. It could be argued that no-one has taken his place because they don't want their scientific achievements belittled or ignored by the senior science establishment: much better to claim they are a scientist with a sideline in presenting, rather than a communicator with a science background. So in this celebrity-obsessed age, is it better to be a scientific shrinking violet?

At this point you might have noticed that I've missed out Brian Cox (or Professor Brian Cox as it states on the cover of his books, just in case you thought he was an ex-keyboard player who had somehow managed to wangle his way into CERN.) If anyone could wish to be Sagan's heir - and admits to Sagan as a key inspiration - then surely Cox is that scientist. With a recent guest appearance as himself on Dr Who and an action hero-like credibility, his TV series having featured him flying in a vintage supersonic Lightening jet and quad biking across the desert, Cox is an informal, seemingly non-authoritative version of Sagan. A key question is will he become an egotistical prima donna and find himself divorced from the Large Hadron Collider in return for lucrative TV and tie-in book deals?

Of course, you can't have science without communication. After all, what's the opposite of popular science: unpopular science? The alternative to professionals enthusing about their subject is to have a mouth-for-hire, however well presented; delineating material they neither understand nor care about. And considering the power that non-thinking celebrities appear to wield, it's vital that science gets the best communicators it can, recruited from within its own discipline. The alternative can clearly be seen by last years' celebrity suggestion that oceans are salty due to whale sperm. Aargh!