In these dark times, when some moron (sorry, non-believer in scientific evidence) can easily reach large numbers of people on social media with their conspiracy theories and pseudoscientific nonsense, I thought it would be an apt moment to look at the sort of issues that block the initiation, development and acceptance of new scientific ideas. We are all aware of the long-term feud between some religions and science but aside from that, what else can influence or inhibit both theoretical and applied scientific research?

There are plenty of other factors, from simple national pride to the ideologies of the far left and right that have prohibited theories considered inappropriate. Even some of the greatest twentieth century scientists faced persecution; Einstein was one of the many whose papers were destroyed by the Nazis simply for falling under the banner 'Jewish science'. At least this particular form of state-selective science was relatively short-lived: in the Soviet Union, theories deemed counter to dialectical materialism were banned for many decades. A classic example of this was Stalin's promotion of the crackpot biologist Trofim Lysenko - who denied the modern evolutionary synthesis - and whose scientific opponents were ruthlessly persecuted.

Even in countries with freedom of speech, if there is a general perception that a particular area of research has negative connotations then no matter how unfounded, public funding may be affected likewise. From the seemingly high-profile adulation of STEM in the 1950s and 1960s (ironic, considering the threat of nuclear war), subsequent decades have seen a decreasing trust in both science and its practitioners. For example, the Ig Nobel awards have for almost thirty years been a high-profile way of publicising scientific projects deemed frivolous or a waste of resources. A similar attitude is frequently heard in arts graduate-led mainstream media; earlier this month, a BBC radio topical news comedy complemented a science venture that was seen as "doing something useful for once."

Of course, this attitude is commonly related to how research is funded, the primary question being why should large amounts of resources go to keep STEM professionals employed if their work fails to generate anything of immediate use? I've previously discussed this contentious issue, and despite the successes of the Large Hadron Collider and Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, there are valid arguments in favour of them being postponed until our species has dealt with fundamental issues such as climate change mitigation.

There are plenty of far less grandiose projects that could benefit from even a few percent of the resources given to the international, mega-budget collaborations that gain the majority of headlines. Counter to the 'good science but wrong time' argument is the serendipitous nature of research; many unforeseen inventions and discoveries have been made by chance, with few predictions hitting the mark.

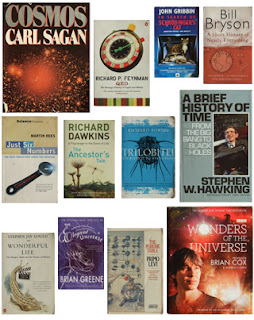

The celebrity-fixated media tends to skew the public's perception of scientists, representing them more often as solitary geniuses rather than team players. This has led to oversimplified distortions, such as that inflicted on Stephen Hawking for the last few decades of his life. Hawking was treated as a wise oracle on all sorts of science- and future-related questions, some far from his field of expertise. This does neither the individuals involved nor the scientific enterprise any favours. It makes it appear as if a mastermind can pull rabbits out of a hat, rather than hardworking groups spending years on slow, methodical and - let's face it - from the outsider's viewpoint what appears to be somewhat dull research.

The old-school caricature of the wild-haired, lab-coated boffin is thankfully no longer in evidence, but there are still plenty of popular misconceptions that even dedicated STEM media channels don't appear to have removed. For example, almost everyone I meet fails to differentiate between the science of palaeontology and the non-science of archaeology, the former of course usually being solely associated with dinosaurs. If I had to condense the popular media approach to science, it might be something along these lines:

- Physics (including astronomy). Big budget and difficult to understand, but sometimes exciting and inspiring

- Chemistry. Dull but necessary, focusing on improving products from food to pharmaceuticals

- Biology (usually excluding conventional medicine). Possibly dangerous, both to human ego and our ethical and moral compass (involve religion at this point if you want to) due to both working theories (e.g. natural selection) and practical applications, such as stem cell research.

Talking of applied science, a more insidious form of pressure has sometimes been used by industry, either to keep consumers purchasing their products or prevent them moving to rival brands. Various patents, such as for longer-lasting products, have been snapped up and hidden by companies protecting their interests, while the treatment meted out to scientific whistle blowers has been legendary. Prominent examples include Rachel Carson's expose of DDT, which led to attacks on her credibility, to industry lobbying of governments to prevent the banning of CFCs after they were found to be destroying the ozone layer.

When the might of commerce is combined with wishful thinking by the scientist involved, it can lead to dreadful consequences. Despite a gathering body of evidence for smoking-related illnesses, the geneticist and tobacco industry spokesman Ronald Fisher - himself a keen pipe smoker - argued for a more complex relationship between nicotine and lung disease. The sector used his prominence to denigrate the truth, no doubt shortening the lives of immense numbers of smokers.

If there's a moral to all this, it is that even at a purely theoretical level science cannot be isolated from all manner of activities and concerns. Next month I'll investigate negative factors within science itself that have had deleterious effects on this uniquely human sphere of accomplishment.